The human exposome refers to the many environmental exposures experienced throughout our lifetime, starting from conception and pregnancy. The exposome approach promotes a fundamental shift in studying environmental impacts on health, moving research from a ‘one exposure, one disease’ approach, to one that is more comprehensive and consistent with the hundreds of exposures most humans now experience.

Early life stages are a key period of our development during which we are highly susceptible to environmental damage, often with life-long health consequences. This makes this period an important starting point for addressing environmental exposures.

A recent study explored the environmental factors that are most likely to affect children’s health, ranking the impact of these factors. Building from that work, a follow-up study set out to identify the dose-response relationships of those factors on children’s health.

In a recent EDC Strategies Partnership webinar, Dr. Rémy Slama explained the methodology and results of those studies.

Ranking impacts: A plausibility database

In the initial study, researchers created a systematic approach to assess the overall evidence connecting exposure risks to cardiometabolic, neurodevelopmental, respiratory, and other birth and child health outcomes. They compiled a “plausibility database” characterizing the level of evidence (LoE) linking 88 different environmental factors to children’s health outcomes.

The study considered findings from epidemiological, toxicological, and mechanistic studies. The window of exposures included were from the prenatal period through adolescence. Exposure factors were paired with specific health outcomes, and the strength of each linkage was rated based on the scientific evidence reviewed. The likelihood of a specific health outcome resulting from an exposure was designated on a scale from “very unlikely” to “very likely.”

Many "likely" linkages

An example of a factor-outcome pair is PCB exposure with lower birth weight (which was found to be very likely). The study considered 88 chemical and physical factors, including:

- Air pollutants

- Tobacco smoke

- Pesticides

- Bisphenols

- Parabens

- Phthalates (such as DEHP)

- Metals, including lead and cadmium

- Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)

- Physical factors (such as noise, temperature, and access to green spaces)

A total of 611 factor-outcome pairs were considered. The study found 127 factor-outcome pairs that had an overall LoE of 60% or more, and were therefore found to be likely or very likely. Those 127 pairs involved 49 different factors/exposures. Some exposures were associated with multiple adverse health outcomes. These included the following:

8 outcomes: HCB (a pesticide), PCBs, temperature (heat)

7 outcomes: PFOA (a PFAS)

6 outcomes: PFOS (a PFAS), cotinine (from tobacco smoke)

5 outcomes: arsenic, lead

4 outcomes: BPA, BPS, PFNA (a PFAS), and PM2.5

3 outcomes: DDT (including DDE and DDD), PFHxA (a PFAS), PFDA (a PFAS), UV radiation

Dose-response relationships

A follow-up study focused on the 78 substance-outcome pairs (excluding air pollution and physical factors) that were likely or very likely. This study sought to identify which pairs had known dose-response relationships that had been identified in existing epidemiological studies in children.

Fifty of the substance-outcome pairs had known dose-response relationships. For the remaining 28 pairs, very limited dose-response relationship data is available in the existing research. This highlights an important knowledge gap.

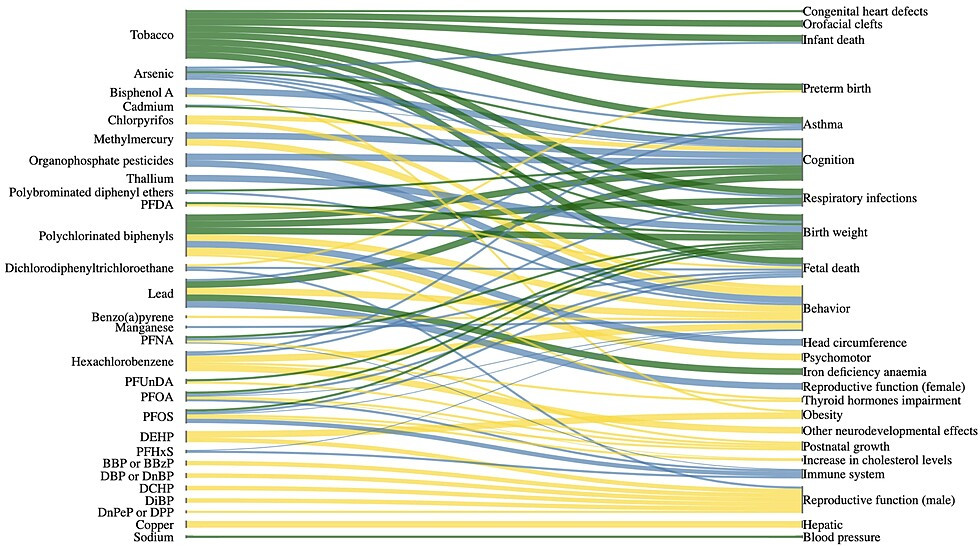

Below are the identified chemical exposures and their likely or very likely health outcomes in children. Those without identified dose-response relationships are in yellow:

Figure 1. Likely or very likely exposure-outcome pairs.

Source: Rocabois A et al. 2024. Chemical exposome and children health: Identification of dose-response relationships from meta-analyses and epidemiological studies. Environmental Research 262:1, 119811.More protective policies needed

These studies identified strong concerns about the effects on children’s health of many specific risk factors.

Dr. Slama noted that some of the identified risk factors are now strongly regulated (such as PCBs, PFOA, and PFOS via the Stockholm international convention). However, for others, regulations are more limited or piecemeal (such as PFAS other than PFOA and PFOS, and phenols (including parabens)). This highlights the need for more protective policies around these risk factors.

The project also identified which risk factors did not have known dose-response relationships, which could be areas for future research. Reducing the health burden attributable to these environmental exposures requires policies designed to reduce exposures.

Health Impact Assessment (HIA) studies are an important tool for prioritizing the most harmful chemicals. Studies that establish dose-response relationships are an important part of HIAs. Twenty-eight substance-outcome pairs which were ranked as likely or very likely to cause harm lack an established dose-response relationship. More research on these relationships could help inform better policies.

For more on these studies, see our webinar Children's Health: Assessing impacts of the exposome.

In addition to the two studies discussed here, a separate follow-up study to the plausibility database was also conducted, which analyzed the evidence for air pollution and physical factors: Urban environment and children’s health: An umbrella review of exposure response functions for health impact assessment .

This organizational blog was produced by CHE's Science Writer, Matt Lilley.